governance

Political Economy Analysis for Decision-Making in Forestry

CHALLENGE

Forest governance reforms create “winners” and “losers.” Losers oppose the reforms and will likely sabotage the reform process. Would-be reformers must offset the resistance of losers. This is not easy since the losers are, typically, a small, well-entrenched and politically powerful group that can organize and act forcefully, while potential winners are part of a much larger and more scattered group, and less capable of organizing themselves for collective action, even when they stand to be directly affected directly. The success of reform often hinges on being able to overcome the resistance of the losers, strengthen demand for good governance and get the support of potential winners. But how can a development agency, in practice, increase the probability of success of reform initiatives?

Thus, a review of political economy analysis (PEA), or the technique “concerned with the interaction of political and economic processes in a society”, was carried out to assess the applicability of different PEA frameworks onto different forestry governance development projects.

APPROACH

This activity examines a range of political economy issues arising from forest governance reform attempts, and offers suggestions on how resistance can be mitigated and the support from would-be winners strengthened to reduce the risks of sabotage. More specifically, the activity produces:

- A detailed review of literature and available experiences in forestry and other relevant sectors

- A focus group workshop at the World Bank to gather inputs from Bank staff on their experience and understanding of political economy issues and hands on practice on one of the political economy frameworks.

RESULTS

The final paper "The Political Economy of Decision-making in Forestry: Using Evidence and Analysis for Reform" is now available. The report is based on two workshops , featuring Net-Map, the most practical and result –proven technique in governance reform.

The paper reviews eight PEA approaches: DFID’s Drivers of Change, ODI’s sector level analysis, The World Bank Group’s Political Economy of Policy Reform and Problem-driven Governance and Political Economy Analysis, Strategic Governance and Corruption Analysis, SIDA’s Power analysis, the Agent-Based Stakeholder Model, and Net-Map. Each of these approaches is analyzed based on four factors, pertinent to the forest sector: practicality, relevance, robustness and adaptability.

- Practicality: encompassing factors such as time, resources, or capacity.

- Relevance: refers to usefulness of the technique for project planning, implementation, and monitoring or evaluation.

- Robustness: refers to credibility and replicability of the technique.

- Adaptability: refers to how flexible the technique is, at different level of analysis and applicability of the technique multi-sector analysis.

Based on the specificity of the project that each of the technique is chosen, however, there is only one framework that has been directly applied in forest sector (Net-Map). Understanding that PEA can lead to long term impact, one recommendation from the report is to promote the use of PEA at corporate level, and building up evidence based on how PEA contributes to better outcomes in the sector.

For stories and updates on related activities, follow us on Twitter and Facebook, or subscribe to our mailing list for regular updates

For stories and updates on related activities, follow us on twitter and facebook , or subscribe to our mailing list for regular updates.

Last Updated : 06-16-2024

Share

Related Links

Assessing Forest Governance: A practical guide to data collection analysis and use

Evaluando La Gobernanza Forestal: Una guia practica para la recoleccion analyisis y uso de datos

Evaluation de la gouvernace forestiere

Assessing and Monitoring Forest Governance

Attachments

PROFOR_AssessForestGov_ESP May 13 final_0_0.pdf

FAO-PROFOR Gov Data Collection Guide web 7-17-14_0_0.pdf

Authors/Partners

Phil Cowling, Kristin DeValue, and Kenneth Rosenbaum

Developing Guidance on Forest Governance Data Collection for Assessment and Monitoring

CHALLENGE

Good forest governance has a central role in achieving sustainable forest management. It is also critical to ensure the effectiveness of plans to reduce greenhouse gas emissions from deforestation and forest degradation in developing countries (REDD), as well as to ensure the effectiveness of efforts to reduce illegal activities in the forest sector.

Assessment and monitoring of governance are essential tools in promoting reforms to achieve better forest governance. Making available a compendium of evidence-based approaches to forest governance data collection could help countries decide between different options as they respond to various requirements, for example, such as those arising from the Voluntary Partnership Agreement (a bilateral trade agreement between the EU and some timber-producing countries) or from REDD+.

APPROACH

PROFOR has developed a common framework for assessing and monitoring forest governance, in collaboration with the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations and other partners, including the World Resources Institute, Chatham House, the European Forest Institute, and the UN-REDD Programme. PROFOR also piloted an approach for collecting data, based on questionnaires scored by multiple stakeholders, which so far has been used in a range of countries: Uganda, Burkina Faso, Kenya, Russian Federation, Madagascar, Democratic Republic of Congo and Liberia. However, this approach is only one of many indicator and data collection options available to practitioners.

To improve the process, PROFOR has a new project that aims to compile a compendium of approaches to forest governance data collection, to provide practitioners with a menu of options that is customizable to specific contexts. The guide on data collection approaches will be accompanied by a library of forest data collection initiatives that have been field-tested in one or more countries. To the extent possible, the guide and library will be updated as additional field experiences become available.

The production of this menu of options is expected to strengthen collaboration and cooperation between the World Bank and its partners in the area of forest governance diagnostics, to foster agreement on common indicators for forest governance, and to reduce multiple reporting.

RESULTS

In June 2012, in Rome, thirty-five international and national experts gathered to discuss common issues in governance assessment and monitoring, and considered the value of producing resource materials for people measuring forest governance. The meeting resulted in the need for developing guidance for forest governance data collection and the creation of the Core Expert Group on Forest Data Collection. In November 2012, the first core group meeting took place in Brussels and produced an outline of the guidance—“a practical guide to measuring forest governance for assessments and monitoring”—and a plan for collecting tools and cases in this area. In June 2013, PROFOR, FAO, the UN-REDD Programme, WRI and others convened a second core group meeting. This meeting reviewed a draft guide based on the outline and discussed next steps.

The guide was launched in June 2014, at COFO 22, in Rome. This guide presents a step-by-step approach to planning forest governance assessment or monitoring, collecting data, analyzing it, and making the results available to decision makers and other stakeholders. It also presents five case studies to illustrate how assessment or monitoring initiatives have applied the steps in practice, and it includes references and links to dozens of sources of further information.

For stories and updates on related activities, follow us on Twitter and Facebook, or subscribe to our mailing list for regular updates.

For stories and updates on related activities, follow us on twitter and facebook , or subscribe to our mailing list for regular updates.

Author : Phil Cowling, Kristin DeValue, and Kenneth Rosenbaum

Last Updated : 06-16-2024

Share

Related Links

Forest Sector Public Expenditure Reviews: Review and Guidance Note

Benchmarking Public Service Delivery at the Forest Fringes in Jharkand (India)

Reforming Forest Fiscal Systems

Attachments

Forest-Sector-PER-review-PROFOR.pdf

Authors/Partners

Martin Fowler with Patrick Abbot, Stephen Akroyd, John Channon, Samantha Dodd (Oxford Policy Management and LTS International).

Forest Sector Public Expenditure Reviews (Toolkit)

Evaluating the effectiveness of public spending in the forestry sector: lessons from global good practices

CHALLENGE

Public expenditures in the forest sector arise from the need to maximize development outcomes and enhance livelihoods, conserve a variety of local and global public goods, set an attractive investment climate to leverage private investment, and contribute to the costs of forest administration. Yet the sector is typically poorly funded in most developing countries.

Lack of adequately qualified staff, lack of funds to carry out essential supervisory operations and lack of equipment are symptoms of ineffective budget planning and allocation. Poorly paid staff have few incentives to execute their duties responsibly and may be tempted to indulge in corrupt and illegal practices. In the end, mismanaged forests compromise development and environmental goals.

APPROACH

Sectoral public expenditure reviews can help diagnose spending problems and help countries develop more effective and transparent budget allocations that promote growth and reduce poverty.

To ensure that sectoral reviews are based on effective tools (tracking surveys, citizen report cards, etc) and translate into successful policy and spending reforms, PROFOR commissioned a stock-taking of public expenditure reviews in the forests sector. The authors examined global best practice examples from other sectors and made recommendations based on this analysis.

The guidance note covers the issues to be considered during the preparation phase of a forests sector PER, and in drawing up the Terms of Reference (an example ToR is provided), the analysis that should be contained within the report, and a proposed structure for the report.

FINDINGS

The review finds that, globally, very few forest sector PERs have been undertaken to date. Of the 61 PERs reviewed, only 14 focused to any degree on forestry. Of these, 11 were part of an FAO programme of sustainable forest development, where the principal focus was on aspects of forest revenue, with only limited analysis of sector expenditures.

The principal findings of the review of PER literature are as follows:

- The definition of ‘forestry’ and the ‘forest sector’ differs considerably between studies.

- There are considerable inconsistencies between policy priorities and planned budget allocations to the forest sector.

- Data problems were a common feature of the PERs.

- In almost all of the cases reviewed, only a small proportion of the national budget is allocated to the forest sector.

- Many of the PERs reveal low disbursement rates against approved budgets.

- The importance of NGO expenditure and involvement in the forests sector is understated.

- Capital investments are undertaken without consideration of the associated recurrent spending requirements to adequately maintain these investments.

- Operations and maintenance (O&M) funding in forestry departments is inadequate.

- Few attempts have been made in the PERs reviewed to link public sector expenditure to outcomes.

- There is limited analysis of the efficiency and effectiveness of forestry expenditures.

RESULTS

PROFOR and Oxford Policy Management hosted a half-day workshop on December 14, 2010, in Washington DC. The objective of the workshop was to present the initial findings from the Forest PER survey, to discuss some of the best practices which have emerged from this review, and to seek wider feedback about the utility of the draft guidance note, and how it can be made more useful to sectoral practitioners. The review and guidance note were finalized in January 2011 and published formally in July 2011.

In a second phase, individual countries will customise the guidelines to meet their specific requirements and experiences with piloting the guidelines will be used to revise the guidance note.

For stories and updates on related activities, follow us on twitter and facebook , or subscribe to our mailing list for regular updates.

Author : Martin Fowler with Patrick Abbot, Stephen Akroyd, John Channon, Samantha Dodd (Oxford Policy Management and LTS International).

Last Updated : 06-16-2024

Share

Related Links

Artisanal and Small Scale Mining: A Summary (PDF- 24 pages May 2013)

ASM-PACE Global Solutions Study

Liberia Case Study (June 2012)

ASM-PACE Methodological Toolkit (June 2012)

Field Notes: Green gold for Gabon (Nov. 2012)

Record Gold Prices Drive Deforestation in Peruvian Amazon

Attachments

ASM_PACE-GlobalSolutions_1.pdf

Authors/Partners

WWF, Fauna and Flora International, and Estelle Levin Ltd, for the World Bank Africa Region.

Impact of Artisanal and Small Scale Mining in Protected Areas

CHALLENGE

Artisanal and small scale mining (ASM) is an important source of income for millions of poor people around the world. The past decade has seen increasing numbers of individuals and households turn to ASM, and this trend is likely to grow in the face of high mineral prices, population growth, poverty and climate change. Because ASM activities contribute to poverty reduction in remote rural areas, efforts to simply eradicate the activity tend to fail.

However ASM tends to destroy and degrade forest ecosystems (through habitat destruction, the use of toxic chemicals, pollution of waterways, etc) and threatens the practices on which mining populations depend (for example, gathering firewood, bushmeat hunting, timbering for construction, etc). It is also a growing driver for internal migration and colonization of frontier forest lands that may lead to permanent land clearance.

APPROACH

With PROFOR support, the World Bank's Africa regional staff contracted WWF and Estelle Levin Ltd to conduct studies in Liberia and Gabon to analyze the impacts of artisanal mining activities on high-value natural landscapes and the people who live nearby. Drawing lessons from the assessment of two national parks (Ndangui in Gabon and Sapo National Park in Liberia) and existing literature on succesful park management, the case studies, the global solutions study and the methodolgical toolkit offer recommendations on how to reconcile socio-economic development based on artisanal mining and preservation of important ecological sites.

MAIN FINDINGS

The study looked at 36 countries and found that artisanal and small scale mining was taking place either inside or along the borders of 96 out of 147 protected areas in those countries. In the end, the project looked in more depth at experiences in three countries: Liberia, Gabon and Madagascar (case study is forthcoming) -- see videoclip for findings.

It concluded that military efforts to permanently remove illegal miners from protected areas were not sustainable in the long run (particularly if a source of minerals is well known), and that other solutions could help breach a compromise between conservation goals and mining activities:

- For example, there are potential opportunities to develop sustainable mining through a sustainable supply chain approach, notably in Gabon where miners do not use mercury to extract gold.

- Short of eviction, co-existence and degazetting parts of protected areas are also options that allow negotiated access to mineral resources.

- Although replacing artisanal and small scale mining with large-scale operations may be attractive from a government regulation point of view, they do not offer the same number of jobs that smaller operations do.

The Methodological Toolkit has been designed to help users:

1.Rapidly assess and map environmental, social and economic impacts of Artisanal and Small-scale Mining,with a particular focus on protected areas, critical ecosystems and vulnerable groups.

2.Identify potential solutions and alternative approaches through assessment of past efforts (both successes and failures) to address the identified short- and long-term environmental impacts.

3.Identify and develop measures that can produce concrete improvements in critical ecosystems through sustainable solutions that reduce the environmental and social damage caused by ASM, while building on its economic, social, and empowerment potential.

For stories and updates on related activities, follow us on twitter and facebook , or subscribe to our mailing list for regular updates.

Author : WWF, Fauna and Flora International, and Estelle Levin Ltd, for the World Bank Africa Region.

Last Updated : 06-16-2024

Share

Related Links

Field Notes: The Journey of Forest Governance

Attachments

Governance-RDC_Rapport-23jan 2013_1.pdf

Liberia_Assessment of key governance issues for REDD+_2.pdf

ETAT DE LA GOUVERNANCE FORESTIERE 2012_1.pdf

ForestGovernanceFramework_0_1.pdf

AssessingMonitoringForestGovernance-guide_2.pdf

Authors/Partners

Nalin Kishor and Kenneth Rosenbaum

Assessing and Monitoring Forest Governance

CHALLENGE

In 2009 a World Bank report called Roots for Good Forest Outcomes provided the framework for a comprehensive look at forest governance in terms of five building blocks and their principal components and subcomponents. As such, it provided a better insight into what constitutes “ideal” forest governance.

The next step was to develop a simple and actionable governance diagnostic tool which would help benchmark and pinpoint areas requiring reform, at a time when international initiatives such as FLEGT-VPA and REDD+ are putting pressure on countries to improve governance in the forestry sector.

A good diagnostic tool can establish a baseline for forest governance in specific countries and help identify areas for reform in a non-prescriptive manner, building consensus among stakeholders.

APPROACH

Along with the World Bank, several agencies and NGOs (World Resources Institute, Global Witness, Transparency International and Chatham House for example) have begun developing forest governance monitoring tools. Although these initiatives have been developed for different purposes and with different end users in mind, preliminary comparative analysis of these initiatives has shown that there is considerable concordance.

To avoid duplication of efforts, PROFOR, the World Bank and FAO organized a symposium in Stockholm on 13-14 September 2010 during which various forest agencies agreed to work toward defining a common framework of principles and criteria for assessing and monitoring forest governance. This followed field testing of governance-related questions in Uganda among public servants, academics, journalists, parliamentarians and private entrepreneurs took place in Kampala on 15-16 June, 2010.

In May 2011, an experts' meeting convened to discuss a new document drafted with support from FAO, PROFOR and the European Forest Institute, entitled Framework for Assessing and Monitoring Forest Governance (available on this page). Field testing of this approach in Burkina Faso (with PROFOR support) and by partners in Kenya (Indufor) and the Russian Federation (World Bank) helped define and refine a forest governance diagnostic tool.

RESULTS

This work resulted in a publication: Assessing and Monitoring Forest Governance: A user's guide to a diagnostic tool (available on this page) published by PROFOR in June 2012.

- The tool consists of a set of indicators and a protocol for scoring the indicators. The indicators are in the form of multiple-choice questions about aspects of forest governance. Some cover general features of governance, some touch on specifics, and some serve as proxies for factors that are difficult to assess directly. Taken as a whole, the tool examines forest sector governance broadly, serving as a self-assessment to identify areas deserving improvement.

- Recognizing that local involvement is key to successful reform, the tool’s protocol uses a workshop format, where stakeholders meet to discuss governance and try to come to agreement on scoring the indicators. Putting assessment in the hands of stakeholders promotes discussion, identifies areas of consensus, and builds momentum for change.

- The tool will serve countries or their subdivisions that want to improve governance. The initial diagnosis can be a starting point from which to set priorities for reform, to target some areas for deeper study, or to track the progress of reform efforts. A convincing assessment can even contribute to the desire for reform.

- The tool is flexible, relatively inexpensive to use, and adaptable to many contexts. It can be rolled out in a matter of months.

- Since the guide was published, the approach was used in Madagascar by the German aid agency GIZ and Alliance Voahary Gasy for example. In October 2012, a group of experts selected 63 indicators that seemed pertinent to the country context and organized a two day workshop during which government, private sector and civil society actors participated in different working groups, and produced an overall diagnostic of forest governance in the country. It was also used in November 2012 in the Democratic Republic of Congo (with support from USAID.CARPE, IUCN, FCPF) and in Liberia in April 2013 (with support from FCPF). Workshop reports are available on this page.

For stories and updates on related activities, follow us on twitter and facebook , or subscribe to our mailing list for regular updates.

Author : Nalin Kishor and Kenneth Rosenbaum

Last Updated : 06-16-2024

Share

Related Links

National Timber Yield Tables for Mahogany

Information Management and Forest Governance

Supporting the Global Legal Information Network in Gabon

Attachments

Authors/Partners

Ken Rosenbaum of the Forest Integrity Network (FIN)

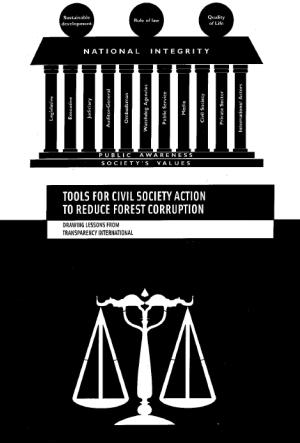

Tools for Civil Society Action to Reduce Forest Corruption

Drawing Lessons from Transparency International (TI)

The forest sector badly needs functioning integrity systems. Corruption promotes illegal logging and trade, and illegal logging is a multi-billion-dollars-per-year problem for the world. Beyond the lost revenues, illegal logging is almost never sustainable. No one has ever quantified the environmental and social harm it causes worldwide.

Transparency International (TI), the world's leading organization in the fight against corruption, pioneered the National Integrity System (NIS) approach to combating corruption. NIS are built on a foundation of social values and public awareness, and rely on various pillars of society providing mutual accountability for corrupt behavior. The pillars include non-governmental actors such as the media and civil society and governmental actors such as the legislature, ombudsmen, and watchdog agencies.

This report -- prepared by Ken Rosenbaum of the Forest Integrity Network (FIN) and published in 2005 -- examines TI's approach to fighting corruption and whether this approach might be applicable to the forest sector. The report concludes that TI's approach to tackling corruption is a constructive and perhaps necessary addition to the fight against illegal logging.

Rosenbaum also carried out a thorough investigation of the TI Corruption Fighters' Toolkit identified tools and tactics from TI's corruption-fighting projects throughout the world to see what might be applied to the forest sector. The result is a straightforward presentation of more than two dozen such tools that could be used by civil society groups to reform forest sector corruption.

For stories and updates on related activities, follow us on twitter and facebook , or subscribe to our mailing list for regular updates.

Author : Ken Rosenbaum of the Forest Integrity Network (FIN)

Last Updated : 06-16-2024

Share

Inside Liberia`s forest sector

The Program on Forests (PROFOR) conducted an institutional capacity assessment survey of the FDA to generate granular level data on the inner workings of the agency in order to position Liberia`s forest sector as an engine for economic growth. 438 FDA employees, or approximately 82% of the staff were interviewed on their experiences and perceptions on the FDA`s operations including human resource management.

The Program on Forests (PROFOR) conducted an institutional capacity assessment survey of the FDA to generate granular level data on the inner workings of the agency in order to position Liberia`s forest sector as an engine for economic growth. 438 FDA employees, or approximately 82% of the staff were interviewed on their experiences and perceptions on the FDA`s operations including human resource management.“The FDA plays a pivotal role in Liberia`s sustainable forest management but faces serious operational challenges especially in human resource management. Improving governance of the forest sector presents significant challenges and requires continuous efforts and long-term engagement. This survey identifies the most necessary interventions and provides a baseline measure of civil service productivity in FDA against which progress can be measured as these interventions get implemented.” Zahid Hasnain, Senior Public Sector Specialist at the World Bank explained.

For stories and updates on related activities, follow us on twitter and facebook , or subscribe to our mailing list for regular updates.

Last Updated : 06-16-2024

Land tenure for forest peoples, part of the solution for sustainable development

By Gerardo Segura Warnholtz. Originally published by the World Bank.

In Science magazine, earlier this year, researchers revealed that ancient forest peoples of the Amazon helped create much of the imposing forest landscape that the world inherits today.

A growing body of evidence shows that the indigenous peoples and other rural communities who now inhabit these ancestral Amazonian "gardens" continue to be vital to their survival.

Today, as never before, cutting-edge tools and technologies allow ranchers to raise cattle and plant oil palm and soy in poor soils, and investors to build dams and roadways in some of the planet’s most remote forests, opening them to exploration and exploitation.

Like other rural peoples in the forests of Central America, Africa and Southeast Asia, many of the indigenous communities of the Amazon are battling for a way of life![]() that depends on keeping the forests standing. But recent evidence suggests that to successfully resist, or merely influence, the impact of powerful economic forces, indigenous and other forest peoples need rights to their lands that are strong and respected, and investments to support their efforts to manage the lands sustainably.

that depends on keeping the forests standing. But recent evidence suggests that to successfully resist, or merely influence, the impact of powerful economic forces, indigenous and other forest peoples need rights to their lands that are strong and respected, and investments to support their efforts to manage the lands sustainably.

These rights confer benefits, many of which will be discussed at the Conference on Community Land and Resource Rights in Stockholm next week, such as improvements in health and education levels, two key goals of sustainable development, and progress in stopping the destruction of rainforests, which governments, donors and investors have promised to do in committing to slow climate change.

In Stockholm, I’ll share findings from a recent study on “Securing Forest Tenure Rights for Rural Development,” which aims to improve understanding of what it takes to advance forest tenure reforms. The study identifies Latin America as far advanced in recognizing local or customary tenure rights. As of 2013, for example, “approximately 39% of the region’s forestlands were owned or controlled by indigenous peoples and local communities.” The record has made the region a model for those advocating for recognition and enforcement of customary land tenure in Indonesia and the forest nations of sub-Saharan Africa.

Yet the research also revealed that, cumbersome regulations, limited institutional capacity, and powerful competing interests continue to block the realization of legitimate customary rights, contributing to insecurity, conflicts, and displacement among some of the world’s poorest rural inhabitants.

Some of the challenges identified in the study include: clashes between government agencies; overlapping land claims that haunt the titling process; and bureaucratic obstacles that continue to prevent indigenous communities from taking part in decisions about the fate of their lands.

The study concludes, however, that laws alone are not enough to ensure recognition and respect for rights![]() ; and it notes that in some countries, a lack of political will seems to be a factor, despite evidence that governments struggle to control illegal deforestation, while investors have become increasingly wary of the high costs of conflict.

; and it notes that in some countries, a lack of political will seems to be a factor, despite evidence that governments struggle to control illegal deforestation, while investors have become increasingly wary of the high costs of conflict.

A risk analysis released last year by the Rights and Resources Initiative, featuring cases from Africa, Asia and Latin America, revealed a significant link between weak land tenure and financial risk for those investing in extractives and the production of commodities. In more than 60 percent of the cases studied, the authors identified failure to respect customary land rights of minorities and Indigenous Peoples as the primary cause of the dispute; in the forestry sector, this rose to 90 percent. The authors concluded that the local communities are, “principally interested in opportunities to continue traditional livelihoods![]() ,” but this does not mean they lack economic value.

,” but this does not mean they lack economic value.

Another study by the World Resources Institute (WRI) suggests that granting secure tenure to indigenous peoples and other rural communities—just in Latin America—could generate billions of dollars over the next 20 years, based on evidence of their ability to protect forests that are among the most carbon-rich in the world.

Some leaders may fear that granting rights to indigenous peoples and rural communities could damage their countries’ economies. Given the chance to address them directly, we would say that, “rather than damaging your economies, you will instead be pioneers on the edge of a new frontier; your countries will become magnets for investors seeking to serve a growing market for conflict-free, deforestation-free commodities. And that you will become known for choosing the path of sustainable development, in partnership with your own people, many of them with roots in the ancient forests that are so vital to the survival of the planet.”

So, it is time to urge decision makers across the world to embrace land rights for their economic benefits![]() ; to recognize that strengthening land tenure can support the goals of economic development, while addressing the risks of investing in regions where land rights are weak.

; to recognize that strengthening land tenure can support the goals of economic development, while addressing the risks of investing in regions where land rights are weak.

For stories and updates on related activities, follow us on twitter and facebook , or subscribe to our mailing list for regular updates.

Last Updated : 06-16-2024

Share

Attachments

Keywords

Authors/Partners

World Bank

West Africa Forest Strategy

CHALLENGE

The Upper Guinea Forest, which covers six West African nations, is being severely threatened by commercial logging, slash-and-burn and plantation agriculture, weak governance, industrial-scale mining, and unsustainable bushmeat hunting. Civil conflict adds a further strain when refugees turn to the forests for shelter and firewood.

At the same time, growing national interest in climate change and forest governance trade initiatives (REDD+, FLEGT) is encouraging radical re-thinking in fields such as timber supply and tree and land tenure. The importance of agriculture, energy security and mining to national growth strategies also has implications for forests, both positive and negative.

Development partners have the opportunity to generalize good practices and build regional capacity to confront the coming challenges in the West-Africa sub-region.

APPROACH

PROFOR supported an effort to analyze the forests sector in five countries (Cote d’Ivoire, Ghana, Guinea (Conakry), Liberia and Sierra Leone) and define elements toward an effective West African forests strategy to ensure conservation and sustainable use of forests, the maintenance of forest ecosystem services, and the fair and equitable allocation of revenues and benefits from forest resources.

RESULTS

"Toward a West African Forests Strategy" was published in draft form in April 2011. It is based on five country studies and a synthesis of regional forests sector issues. Elements from this draft strategy will inform the World Bank's future work on forests for Africa and should be helpful to a variety of development partners and forest stakeholders in defining priority areas of support.

MAIN FINDINGS

Among the country level issues which could benefit from policy support, the report singles out:

- restructuring of forest industry to promote value addition and foster economic growth;

- improving forest governance and public finance management;

- balancing supply and demand issues in export and domestic markets and addressing the issue of ‘illegal’ chainsaw logging;

- support for small and medium forest enterprises and community forestry;

- reforming tree and land tenure so as to favour forest conservation and regeneration;

- reforming revenue sharing arrangements and channelling these so that these provide incentives to farmers and land owners;

- integrating REDD+ and other climate actions into forest policy;

- and improving the sustainability of rural energy (wood fuel & charcoal).

Some of the primarily sub-regional issues identified in the strategy include:

- improving the governance of cross border trade in a context of FLEGT, and helping to harmonize sub-regional trade policies;

- enhancing the geographical information and forest inventory data available for sub-regional policy making and trade controls;

- institutional capacity building to support sub-regional policy coherence;

- investing in the cross-border dimensions of protected area management;

- and developing awareness of the extra-sectoral implications of forest policies across the sub-region.

For stories and updates on related activities, follow us on twitter and facebook , or subscribe to our mailing list for regular updates.

Author : World Bank

Last Updated : 06-16-2024

Share

Attachments

Strategies for enforcing wildlife trade regulations in Mongolia 2010_0.pdf

Wildlife Trade Survey Final Report Nov08_0.pdf

Keywords

Authors/Partners

Wildlife Conservation Society, World Bank East Asia and Pacific Region, Netherlands-Mongolia Trust Fund for Environmental Reform

Wildlife Trade Law Enforcement in Mongolia

APPROACH

With support primarily from the Netherlands-Mongolian (NEMO) Trust Fund for Environmental Reform and the World Bank’s Forest Law Enforcement and Governance (FLEG) trust fund, the Wildlife Conservation Society (WCS) had been providing technical assistance focused on detecting and taking actions against illegal wildlife trade in Mongolia. The objective of subsequent technical assistance funded by the FLEG Trust Fund (later part of PROFOR) was to assess the gaps in current laws and regulations which hinder or prevent effective wildlife trade law enforcement, and strengthen local capacity to protect species such as the grey wolf, red fox, marmot, brown bear and Eurasian badger.

RESULTS

The project produced a number of results including:

--Reorganization of the Multi-Agency wildlife trade crime unit which conducts joint inspections in Ulaanbaatar markets on wildlife trade and its parts and products.

--Increased public awareness of the risks of illegal wildlife trading. A ‘Special Call’ placed in 6 national newspapers as well as additional TV coverage and debate resonated with the public.

--Increased media awareness. Recommendations to the media concerning advertisements of wildlife parts and products were followed by a large decline in wildlife advertising in Zar Medee and Shuurhai Zar newspapers.

--Facilitated amendments to the Hunting Law.

--Developed extensive Guidelines for Wildlife Law Enforcement.

For stories and updates on related activities, follow us on twitter and facebook , or subscribe to our mailing list for regular updates.

Author : Wildlife Conservation Society, World Bank East Asia and Pacific Region, Netherlands-Mongolia Trust Fund for Environmental Reform

Last Updated : 06-16-2024